[CATEGORIES: Literature, Lapham’s Quarterly, Reading, Book Review]

[Click HERE to see my previous posts referencing Lapham’s Quarterly.]

[Some of LQ’s contents are available free.]

[L.Q. cover and art from L.Q. Winter 2017: Home.]

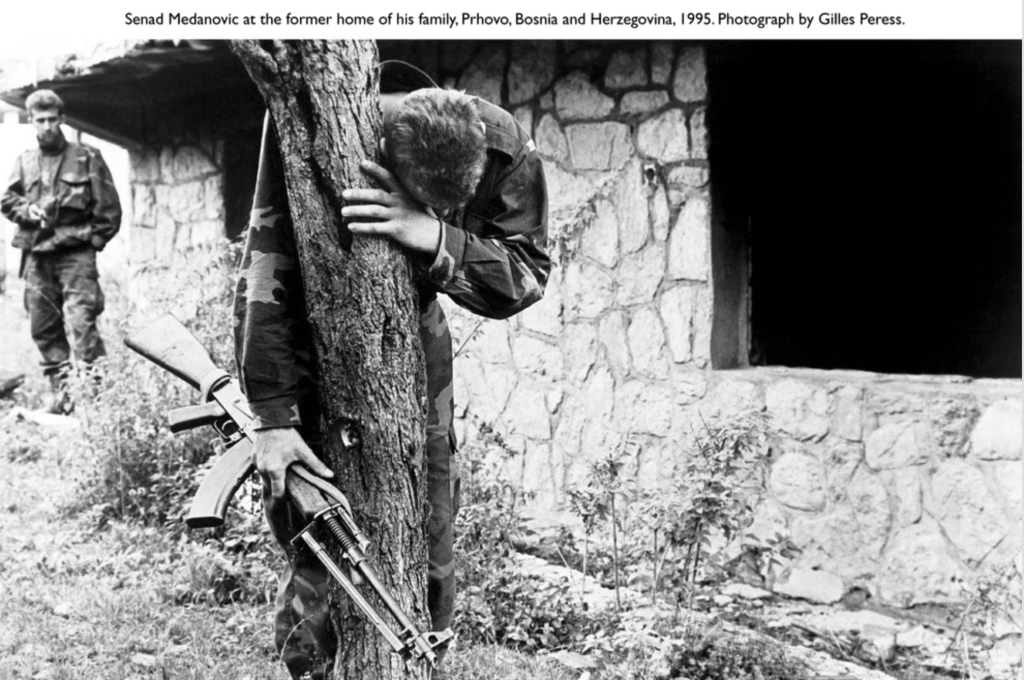

Run, don’t walk, to your nearest computer (presuming you don’t possess a copy of L.Q. HOME) (I know who you are) and READ READ READ the essay Brontosaurs Whistling In The Dark. Here is an internet link: http://www.laphamsquarterly.org/home/brontosaurs-whistling-dark . This 15-page essay (easy reading, pictures and side quotes interspersed) is highly pertinent as I write in early February 2016. It’s about immigrants in 2015 Germany (HOME-less), an example of how they live, Angela (hard G) Merkel’s interaction, and generally what a fine mess it all is.

Don’t get me started on that whole question, but as long as you ask, my preference would be that most of us live in our countries of origin, with orderly exchanges in all border directions for work, study, visiting, and residence. I live in a dream world. Who can blame millions of people for running from unspeakable, unthinkable horrors as madmen on all sides try to reduce any semblance of a structure to particles of dust, along with the flesh and blood inhabiting therein.

Toward the end of the essay the author writes:

“When I was young, in the 1960s, I wrote

an essay deploring the “apocalyptic sensibility,”

which foresaw in every essentially political dis-

agreement the end of the world. I still deplore it.

But I now have something very like that sense.

It has been obvious for decades, at least since

the year 2000, that Western civilization, per-

haps mankind itself, is in jeopardy from various

problems and directions. People tend to adopt

one or more of these problems as political causes

(pollution, energy consumption, global warming,

inequality, nuclear war, racism), which it is

their moral obligation to resolve. I believe that

one serious threat, intended as a humane solution,

has become the attempt to absorb distant

foreign multitudes into what had been fairly

homogenous and stable cultures. (p. 204)

Aye, there’s the rub (thank you William). This massive influx of people is upsetting my homogeneity and stability. On the other hand if my house is exploding, burning, and falling on my head I’m quite likely going to beat down my neighbor’s door to get into his unscathed house and away from mine.

There are noteworthy German language lessons in the essay, most quotes from Angela.

“Wir schaffen das.”

“We will do it”

Regarding which the author ponders:

“…the question as formulated by Chancellor Merkel

remains: do we have a responsibility toward

people seeking asylum from wars in their own

countries, and if so, what are we obliged to do?

People have strong positions. The situation, even

the definition of the problem, seems far from

clear. What did seem clear to me, from the day

of Merkel’s humane, optimistic declaration, was

that the policy, no matter how defined, could not

possibly work.” (p. 191)

“Du kannst das schon schaffen.”

“You can do it.”

“…is something one might say to a child about any task… The undertaking Chancellor Merkel was suggesting (on behalf of herself, of Germany, of Europe) was vast, unprecedented. …migration to Europe from Africa and the middle East was already in the millions.” (p. 192)

“Merkel said, “If we must now begin to apologize for having, under dire circumstances, shown a friendly face, then this is not my country.” (p. 192)

“Dann is das nich mein Land.”

“Fluchtlinge.” (Umlaut over the ‘u’.)

“People fleeing.”

“Nun sind sie halt da.”

“Now they are simply here.”

They have been here for some time. Working in Britain late last century I frequented prolific Indian restaurants as I would Chinese in the U.S. On a visit to Norway in 1992 the Middle Eastern presence did not go unnoticed. Our new President Trump’s squabble with Australian Prime Minister Turnbull over refugee transfers led me to find that these mostly male refugees are housed in fenced compounds on Pacific Islands off Australia. Should the U.S. accept them and do the same, perhaps on Kodiak Island or the Aleutians, but not Santa Catalina or Hawaii? Are they prisoners as much as refugees in their present circumstances?

Note that online this essay title begins with ‘Brontosaurs’ but that word is omitted in the print issue title and text. A 22-page ebook of the article is available on Amazon so I can only assume L.Q. condensed the original as it does the other extracts.

Speaking of HOME as we were, what was the question?

Stated in L.Q. every issue: “Many of the pages in this issue have been abbreviated without the use of ellipses; some punctuation has been modified, and while misspellings have been corrected, archaic grammar and word usage remains unchanged. The words are faithful to the original texts.”

Therefore, not only are the 75-odd extracts in each issue a fragment of a work, each extract is possibly a condensed version of that fragment. It’s a Reader’s Digest spanning time on a theme rather than the R.D. buffet of contemporary subjects.

A friend stopped subscribing and reading L.Q. perhaps because the fragments of a fragment are too time-consuming to digest (sorry) in this age of information overload.

“I gave up subscribing to laphams since I had gotten so far behind and I have a friend that gives me great summaries of what seems important…”

I’m not going to get into the overload subject. That’s a theme for another L.Q. and they’ve already done an issue on Communication. (Coincidentally I just came across a blog post about the Age of Acceleration and slow reading. https://toffeefee.wordpress.com/2016/06/03/reading-fast-and-slow/ Noteworthy as well is his reply to my comments on reviews: “We are maybe old fashioned, but on the other hand it’s as well important really to read this book and not only what the media tell you about it. With this second hand information we delegate our thinking.”) I like that. Don’t delegate your thinking.

I stumbled into the digest aspect because I wanted to share an extract on Home with my friend and it’s not available in L.Q. online. I googled a first paragraph phrase and found it in Google Books but noticed the two page extract from L.Q. I was searching was spread over seven pages of the original book. Eight paragraphs extracted, chopped if you will, with numerous whole paragraphs in between just dropped. Fragments of fragments. That is the purpose, just be advised and aware.

Rather than telling you to go to Google Books dot Com, search on Home Comforts by Cheryl Mendelson, go to page 4 and starting where it says “My maternal grandmother was a fervent housekeeper in her ancestral Italian style,” read through page 10 (pages 8 and 9 are omitted and seem to be also from the L.Q. extract) (even you hugely voracious readers are not expected to do all that, and I know who you are), here are a few bits of the extract of the fragment in L.Q. I found notable:

“My maternal grandmother was a fervent

housekeeper in her ancestral Italian style, while

my paternal grandmother was an equally fer-

vent housekeeper in a style she inherited from

England, Scotland, and Ireland. In one home I

heard Puccini, slept on linen sheets with finely

crocheted edging rolled up with lavender from

the garden, and enjoyed airy, light rooms with

flowers sprouting in porcelain pots on window-

sills and the foreign scents of garlic and dark,

strong coffee. The atmosphere was open and

warmly hospitable. The other home felt like a

fortress—secure against intruders and fitted

with stores and tools for all emergencies. There

were Gay Nineties tunes on the player piano and

English hymns, rooms shaded almost to dark-

ness against real and fancied harmful effects of

air and light, hand-braided rag rugs, brightly

colored patchwork quilts, and creamed lima

beans from the garden.”

“Being at home feels safe; you have a sense of relief

whenever you come home and close the door behind you,

reduced fear of social and emotional dangers as

well as of physical ones. When you are home,

you can let down your guard and take off your

mask. Home is the one place in the world

where you are safe from feeling put down or

out, unentitled, or unwanted. lt’s where you be-

long, or, as the poet said, the place where, when

you go there, they have to take you in. Coming

home is your major restorative in life.”

“Making a home attractive helps you feel at home,

but not nearly so much as most of us seem to

think, if you gauge by the amounts of money we

spend on home furnishings. In fact, too much at-

tention to the looks of a home can backfire if it

creates a stage-set feeling instead of the authen-

ticity of a genuinely homey place.”

“What really does work to increase the feel-

ing of having a home and its comforts is house-

keeping. Housekeeping creates cleanliness, order,

regularity, beauty, the conditions for health and

safety, and a good place to do and feel all the

things you wish and need to do and feel in your

home. Whether you live alone or with a spouse,

parents, and ten children, it is your housekeeping

that makes your home alive, that turns it into a

small society in its own right, a vital place with its

own ways and rhythms, the place where you can

be more yourself than you can be anywhere else.”

(pp. 156-157)

Mendelson appears in the third section of this issue, those sections being:

Dream Houses

Floor Plans

Moving Days

Moving Days has been the most captivating. Mendelson is followed by Alice Munro’s extract from The Office (“I did get an office,” she later said, “and I wasn’t able to write anything there at all–except that story.” p. 161) and preceded by an excerpt from Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter. I spent some time researching both Sigrid and Kristin on Wikipedia. I trust you Norwegians (you know who you are) have read this in the original language. I’m considering reading the first book, translated, to see if it piques my interest. So many books, so little time.

Women can write, there’s no doubt about that. At least since Enhuedanna (L.Q. Winter 2010: Religion).

Frequent contributor James Baldwin also appears in section three, continuing in 1959 to express his discomfort with being American and black:

“I left America because I doubted my ability

to survive the fury of the color problem here.

(Sometimes I still do.) I wanted to prevent myself

from becoming merely a Negro; or, even, merely

a Negro writer. I wanted to find out in what way

the specialness of my experience could be made to

connect me with other people instead of dividing

me from them. (I was as isolated from Negroes as

I was from whites, which is what happens when

a Negro begins, at bottom, to believe what white

people say about him.) (p. 136)

Section 3 Moving Plans begins with an account of Syrian families living in bombed building basements and cemetery tombs, running from any and all fighters. They would die for a cot in a German refugee warehouse. Sadly many will.

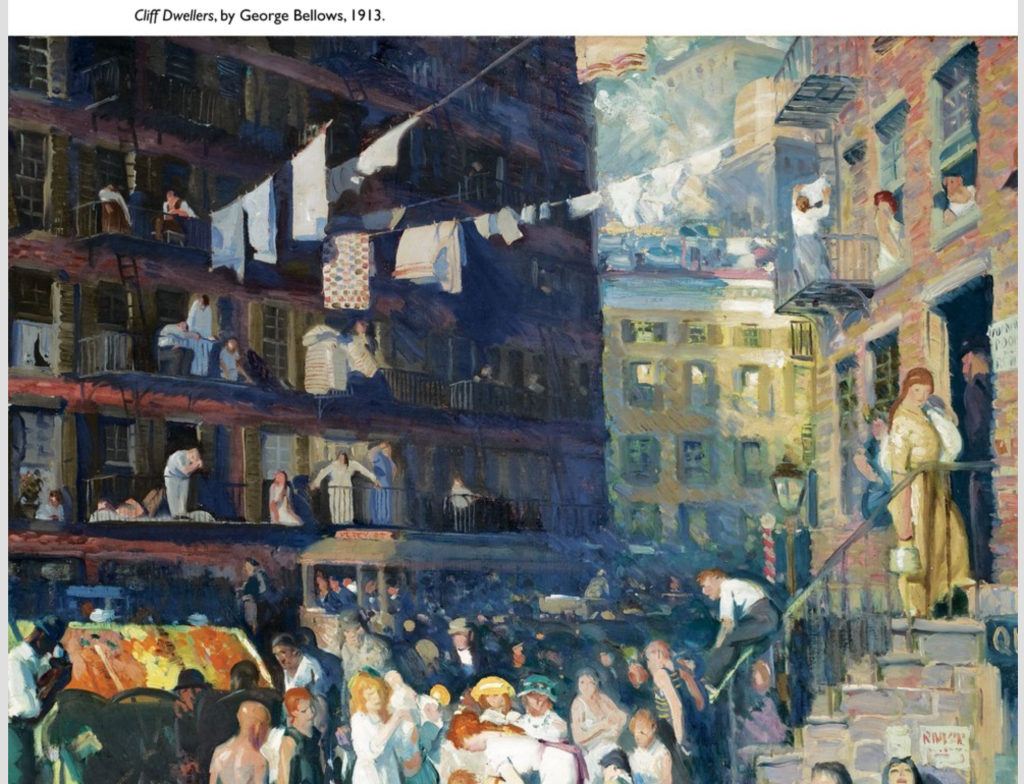

Toni Morrison has a thoughtful excerpt in Section 2 Floor Plans on living in Harlem, the predominantly black section of New York City, in 1927.

“The young are not so young here, and there

is no such thing as midlife. Sixty years, forty,

even, is as much as anybody feels like being

bothered with. If they reach that, or get very

old, they sit around looking at goings-on as

though it were a five-cent triple feature on

Saturday.” (p. 124)

George Orwell surveys distressed housing conditions in 1937 England, shades of Jacob Riis, who earlier in this section is excerpted from How The Other Half Lives, on tenements in 1890 NYC. Riis:

“Their “large rooms were partitioned into

several smaller ones, without regard to light

or ventilation, the rate of rent being lower in

proportion to space or height from the street;

and they soon became filled from cellar to gar-

ret with a class of tenantry living from hand to

mouth, loose in morals, improvident in habits,

degraded, and squalid as beggary itself.”” (p. 87)

I’ve read some of The Other Half. It’s long but eye-opening. Some rented sleeping space was as rudimentary as sitting fully-clothed on stools in a row with arms draped over a rope strung across the room. No wakeup alarm was needed as the landlord would drop the rope if anyone overslept.

Edgar Allen Poe was a stalwart critic of architecture and decor:

“We have no aristocracy of blood, and having

therefore as a natural and indeed as an inevitable

thing, fashioned for ourselves an aristocracy of

dollars, the display of wealth has here to take

the place and perform the office of the heraldic

display in monarchical countries. In America,

dollars being the supreme insignia of aristocracy

their display may be said, in general terms,

to be the sole means of aristocratic distinction

and the populace, looking up for models,

are insensibly led to confound the two entirely

separate ideas of magnificence and beauty. In

short, the cost of an article of furniture has, at

length, come to be, with us, nearly the sole test

of its merit in a decorative point of view.” (p. 102-103)

Holocaust survivor and chronicler Primo Levi is eloquent on his life-long residence in one home:

“Through all its transformations, the apartment

where I live has preserved its anonymous

and impersonal appearance: or at least, that’s

how it looks to us who live in it. But it’s well

known that people are poor judges of everything

that concerns them, of their own personalities,

their own virtues and defects, even their own

voices and faces; others, perhaps, might see it as

deeply symptomatic of my family’s reclusive tendencies

Certainly, I have never consciously demanded

from my home anything more than to satisfy my

primary needs: space, warmth, comfort, silence,

privacy. Nor have I ever consciously tried to

make it mine, to make it resemble me, to embellish

it, enrich it, or trick it up.” (p. 96)

At the end of section one’s Dream Houses (all sections are grouped under Voices In Time) Mark Twain earns my coveted triple asterisk (***) annotation for outstanding excerpt (as did Whistling In The Dark). His childhood memories are beautiful prose:

“I can call back the solemn twilight and mystery of the deep

woods, the earthy smells, the faint odors of the wildflowers,

the sheen of rain-washed foliage, the rattling

clatter of drops when the wind shook the trees,

the far-off hammering of woodpeckers and the

muffled drumming of wood-pheasants…

I can call back the prairie, and

its loneliness and peace, and a

vast hawk hanging motionless in the sky, with

his wings spread wide and the blue of the vault

showing through the fringe of their end-feathers.

I can see the woods in their autumn dress, the

oaks purple, the hickories washed with gold, the

maples and the sumacs luminous with crimson

fires, and I can hear the rustle made by the fallen

leaves as we plowed through them.” (p. 70)

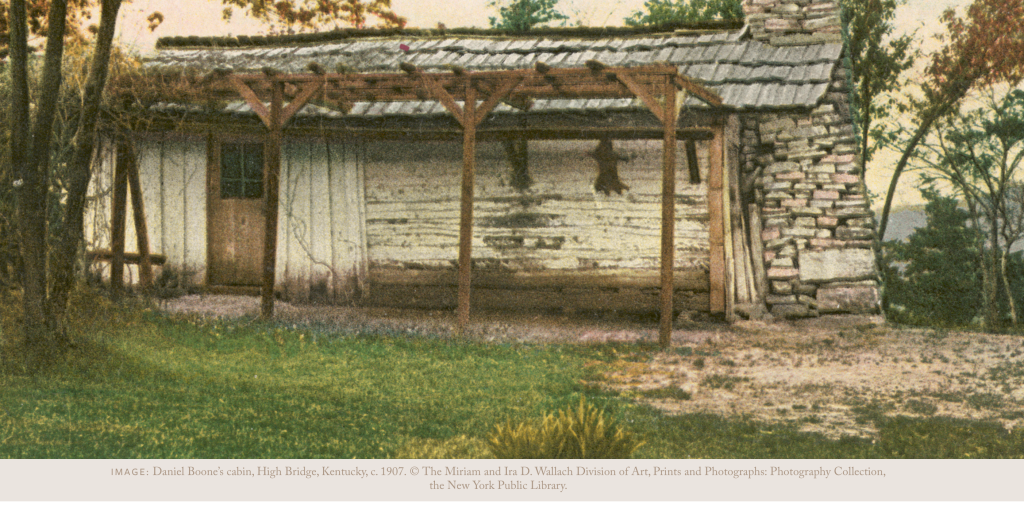

There is a sidebar on house museums (Mt. Vernon, Graceland, the Poe cottage). I love house museums. Seeing how ‘the other half’ lived. The grander the better. Weren’t those the days, living in several laps of luxury. What was that like? My visit to the reconstructed slave shacks at Oak Alley Plantation, Louisiana was an eye-opener as well.

Cookie-cutter homes at Levittown, more poetically descriptive prose (from Phoebe Judson), strict rules at a Disney house development, difficulties for blacks buying and selling near St. Louis. All this is in Dream Houses. Heidegger, Le Corbusier, Daniel Defoe are here too.

Lewis Lapham’s preamble is titled Castles In The Air. Preambles from every issue can be found online at Laphamsquarterly.org. Alluding to the lyrics of the American cowboy song Home On The Range he begins:

“Home in the American scheme of things is a word furnished with as many

meanings and locations as money and mother, God and the flag. A place

always somewhere in mind if not on a map or lost to a bank, there to be

found over a rainbow or bridge, around the next bend in a river or road. Down on

the farm or back in the sticks, crossing the bar or the plate. In the burbs with the

wife and the kids, out on the range with the deer and the antelope, on a centerfold

page in Architectural Digest, at $10,000 a square foot where never is heard a

discouraging word and the skies are not cloudy all day.” (p. 13)

…and ends (same lyric reference):

“Home, home on the home screen, where Facebook and Instagram play, and on laptop and

iPhone the bluebirds of happiness tweet, chirp, and peep all night and all day.” (p. 21)

In between he observes perhaps the downward spiral of housing from shelter to display.

“…the value of the structure was its use, not the profit gained from its sale on a market.”

“A house was a necessity, not a display case of prized personal possessions.” (p. 15)

“The upwardly mobile means of production (railroads, steel mills, electric light, meatpacking plants, oil derricks and pipelines) bettered the lot of their owners but not that of their servants.”

“Two generations of the robber-baron big rich fortified their claims to entity with home furnishings in velvet plush, gold plate, intricately carved mahogany.” (p. 17)

“The wonder-working machinery that in the years 1941-1945 armed and

supplied America’s victories by land and by sea was fitted at war’s end to the

manufacture, distribution, and sale of consumer goods (sturdy and disposable,

essential and superfluous) on a Herculean scale of Hearstian extravagance and

Elvis Presleyan splendor.” (p. 18)

“By the mid-1980s in the American scheme of things home where the

heart is was losing ground to home where the money is. The share of the na-

tion’s income drawn from dividends, interest, and rents surpassed the share

earned in wages; the deindustrialization of America (jobs sent to China or

outsourced to a microchip) was widening the spread between haves and have-

nots, dividing the country into a nation of the rich and a nation of the poor.” (p. 19)

Is he right? You’ll have to read the issue and decide for yourself.

Now that we’ve found our way to the beginning, the issue concludes with an archaeological perspective of Palmyra, Syria as it would have been around 200 A.D. As you know terrorists are now trying to destroy every vestige of its ancient structure. Don’t we want reminders of what the past was like, even if we don’t want recreations of it? We might as well dismantle the Great Pyramids. They are so last millennium, or three or four.

The defense rests.

[For the L.Q. novice or novitiate, the now-standard notes:

1. Since L.Q.’s inception with the Winter 2008 issue its size is always 7″ x 10″ x 1/2-17/32″. It is white-covered with very high quality paper throughout, richly printed reproductions of fine art from time immemorial, exactly 221 pages up to the Sources index at the back.

2. Each issue contains extracts about the title topic from great authors and thinkers spanning all recorded history. It begins with an eloquent, to a fault, preamble/introduction by editor Lewis Lapham. The main body is called Voices In Time and contains 3 or 4 subcategories of the topic with about 25 extracts per section. Noteworthy sidebars and side quotes are liberally distributed throughout and several extended contemporary essays bring up the rear. There are several other small sections every issue.

3. For more details see my previous-posts link or my Goodreads site for earlier reviews of the 30+ issues I’ve read so far. I have 3 archive issues remaining to have read them all once.]

What a well written, far ranging and interesting post that reflects the complexity of the issues we experience today in regard to immigration policy. Thank you Johan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLike

ooops, I just renamed you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha!

LikeLike

Thank you very much for this interesting post and also for the much appreciated shout out! 🙂

Best regards from Norway,

Dina and Klausbernd

LikeLiked by 1 person

Immigration is a real sensitive issue isn’t it John.

LikeLike

It certainly is. It was as timely as ever to be reading this issue of L.Q. with its relevant articles. A quick look at Wikipedia confirms that ‘down under’ has always been a melting pot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Too right John. We have complete suburbs known for different immigrants ie Somalians, Chinese, Lebanese etc. we are fortunate they bring their wonderful cuisines.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting point you raise about the way we use our homes. In mainland Europe people use the streets for leisure and company, every evening the streets are thronged with people but this is not so in UK because everyone goes home, closes the gate and locks the front door as we retreat into isolation.

Interestingly this makes some people suspicious of foreigners. In my last job I worked in a town where there were a lot of immigrants from Portugal and Eastern Europe and one of the frequent complaints by the residents was that the newcomers were hanging around the streets even after the shops were closed. It proved the point that f you don’t understand someone else’s culture then it is certain that you won’t get on.

I wonder what native Americans would think of your idea of staying in our country of origin? In the UK we wouldn’t have had the Romans or the Vikings or the Normans. Solutions to ethnic tensions remain some way off!

Good post, I enjoyed it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your noteworthy comments are additional food for thought. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Conquest seems to have been in human blood for-ever. If we could learn to control that…

LikeLiked by 1 person