[CATEGORIES: Literature, Lapham’s Quarterly, Reading, Book Review]

[Click HERE to see my previous posts referencing Lapham’s Quarterly.]

[Some of LQ’s contents are available free.]

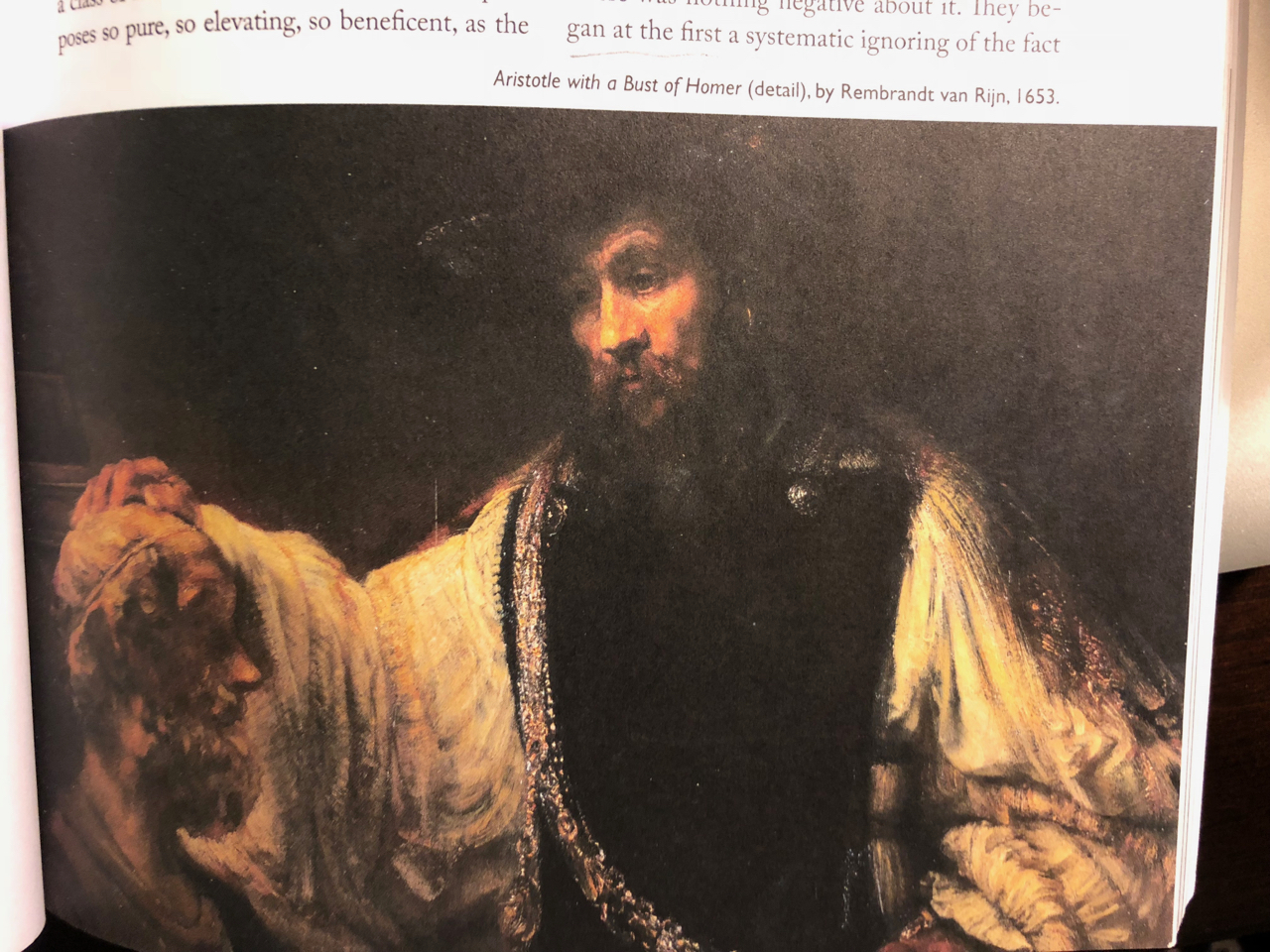

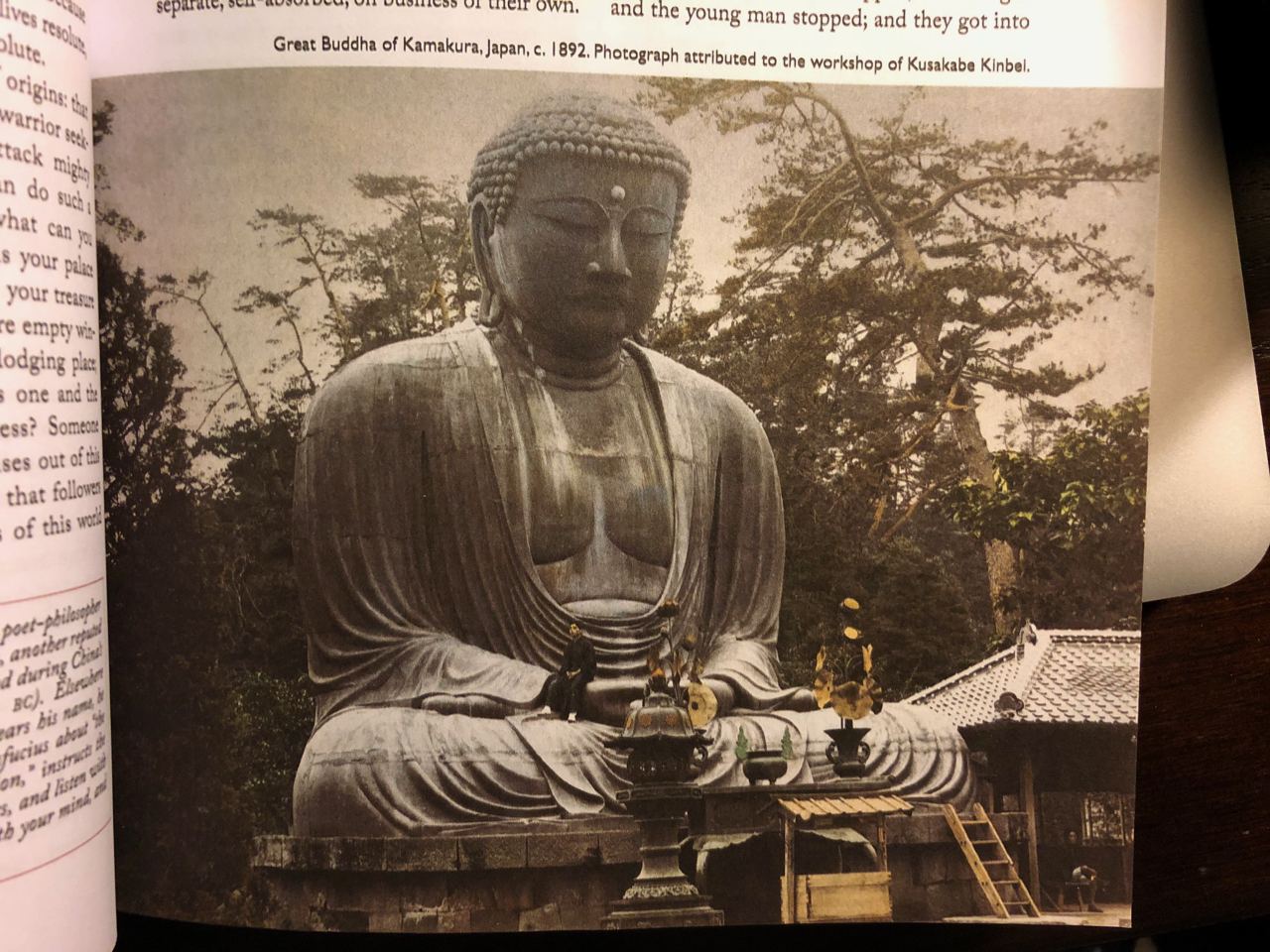

[L.Q. cover and images from L.Q. Winter 2018: States of Mind]

[New to Lapham’s Quarterly? See the standard notes at the end of this review. After 40+ LQ reviews I jump right in.]

I’m mystified, as I often am when reading Lewis Lapham’s Preamble. What was that old elementary school course, or grade on the course? Reading Comprehension. I suspect mine would now be a ‘C’ or a ‘D’, on a descending scale of A, B, C, D, E or F being a Fail, for those of you in other-worldly academic environs.

The preamble title is The Enchanted Loom. States of Mind? Loom? The convoluted and complex brain weaving an abstract tapestry of thought? Perhaps I missed the analogy.

Mr. Lapham has never failed to hurl vocabulary and sentencing I had difficulty grasping. That could be a good thing. The exercise of reaching for meaning and understanding, at whatever comprehension level one happens to be. You grasp what you can.

As a preface to the rest of the issue he does put forward ideas worth pondering. Do we still think, or are we striving and succeeding in abrogating our thinking to machines and Artificial Intelligence? Of course we think, but do we think well, or hard? I’ve often mused that if I were the tribal sage, charged with passing on an ancient oral history to subsequent generations, that the story would be sadly scrambled in my interpretive telling, altering history in one swell foop.

That’s more of a memory issue I suppose. Per St. Augustine in the preamble:

“The power of the memory is prodigious, my God. It is a vast, immeasurable sanctuary. Who can plumb its depths? And yet it is a faculty of my soul. Although it is part of my nature, I cannot understand all that I am…I am lost in wonder when I consider this problem. It bewilders me.” (p. 15)

Mr. Lapham notes that even non-oral history is interpretive:

“History is not what happened two hundred or two thousand years ago. It is a story about what happened two hundred or two thousand years ago. The stories change, as do the sight lines available to the tellers of the tales. To read three histories of the British Empire, one of them published in 1800, the others in 1900 and 2000, is to discover three different British Empires on which the sun eventually sets.” (p. 14)

Oddly, I think, Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk, and Steve Wozniak have spoken out against AI or forms of it, but none of them are included in this issue.

Examples:

http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-30290540

http://www.businessinsider.com/stephen-hawking-elon-musk-sign-open-letter-to-ban-killer-robots-2015-7

I do question a couple of premises.

One: “Mind is consciousness, and although a fundamental fact of human existence, consciousness is subjective experience as opposed to objective reality…” (p. 14) There may be more assertions than words there but I most take issue with ‘consciousness is subjective experience as opposed to objective reality’. Whose subjective experience defines objective reality? As an Ayn Rand reader I’d put it ‘consciousness is awareness of objective reality’. When you want to argue that a rock is not a rock then you are creating a subjective experience. Be careful someone doesn’t hit you with it to improve your clarity and make an impression on your mind.

We did make the whole thing up didn’t we, but how could we not? Being around for millennia with eyes wide open we were bound to name the things we saw, touched, heard. That didn’t change the things of objective reality, it just gave them names. It’s when we got ‘smart’ and wanted to argue about it that we got subjective. I digress.

Two: “We all live in a great reef of collective experience, past and present, that we receive and preserve and modify.” (p. 15, Marilynne Robinson.) Collective experience (-mind, -psyche, -behavior,) all grate on my (subjectively?) individual point of view. We are separate, individual, (sometimes) thinking human beings. We are not some amorphous mass ‘collective’ of connected minds, though Eric Hoffer (True Believers) or Elias Canetti (Crowds) can enlighten us on, as Hoffer put it, The Nature of Mass Movements. We just don’t think well, or hard, often enough. I know this as I’ve had a lot of experience not doing so.

There are many lines in the Preamble that struck a chord:

RE: AI:

“Watson and Alexa can access the libraries of Harvard, Yale, and Congress, but they can’t read the books. They process the words as objects, not as subjects. Not knowing what the words mean, they don’t hack into the vast cloud of human consciousness… …that is the making of once and future beings.” (p. 14)

“America’s democratic republic was founded on the meaning and value of words. So is the structure of what goes by the name of civilization.

Silicon Valley’s data-mining engineers have no use for the meaning and value of words; they come to bury civilization, not to praise it” (p. 17)

On Man as a material thing:

“In digitally enhanced America these days, who among us thinks it shameful to be no different from a material thing? … Not only is being no different from a material thing not shameful, it is the consummation devoutly to be wished–to be minted into the coin of celebrity, become a corporation, a best-selling logo or brand, a product in place of a person.” (p. 18)

The Kardashians? Ellen’s 12 Days of Christmas giveaways? Now there is some bizarre behavior to observe. Objectively of course. Lapham’s issue on Celebrity, Winter 2011, related how celebrity branding has always been with us. Today we have gone beyond the pale, if any longer there are boundaries on acceptable behavior.

“On screen and off, our world grows increasingly crowded with machines of whom we ask what the rich ask of their servants (comfort us, tell us what to do) and on whom we depend to so arrange the world that we can avoid the trouble of having to experience it.” (p. 18)

Robot toys with which children can interact. Ever more realistic inflatables for the lovelorn and disconnected adults, or so I’m told. (We must keep our sense of humor.) Shudder to think people should converse with other people. I lost perhaps the two greatest conversationalists in my life last summer. Others lost these two also. The world is poorer now, trust me.

I don’t feel I’ve moved States of Mind forward yet. But I’m thinking… thinking…

“…it isn’t with machines that men make their immortality. They do so with the powers of mind acquired on the immense journey up and out of the prehistoric mud, drawing on the immense wealth of subjective human consciousness…” (p. 19)

“Our technologies produce wonder-working weapons and information systems, but they don’t know at whom or at what they point the digital enhancements. Unless we find words with which to place them in the protective custody of the humanities–languages that hold a common store of human value and therefore the hope of a future fit for human beings–we surely will succeed in murdering ourselves with our shiny new windup toys.” (p. 21)

Amen Lewis.

[I received an email notice about this issue. “In States of Mind, Lapham’s Quarterly explores the brain, the soul, and consciousness itself—how they connect and where they diverge.” “The Enchanted Loom On the mind’s ability to reinterpret the past and the tenth anniversary of Lapham’s Quarterly.” Ah, that explains it better. Forget everything I just said.]

The Preamble is available online at LaphamsQuarterly.Org. You’re invited to read a tidbit or two and express your thoughts in a comment here.

Quite dense and far-reaching material!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Quite introspective, this issue. I think, I think, therefore…

LikeLike

Aren’t we fortunate to have the leisure to just “think.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s what I was thinking. The Devil’s playground?

LikeLike

I like the thoughts on what is history John Interesting!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agreed. Even today we have a hard time figuring “What just happened?”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person