[CATEGORIES: Literature, Lapham’s Quarterly, Reading, Book Review]

[Click HERE to see my previous posts referencing Lapham’s Quarterly.]

[Some of LQ’s contents are available free.]

[L.Q. cover and images from L.Q. Spring 2018: Rule of Law]

[New to Lapham’s Quarterly? See the standard notes at the end of this review. After 40+ LQ reviews I jump right in.]

“SELF!” I said introspectively, a year or so ago, to gain my attention. “Through the political turmoil before and after the last Presidential election Lapham’s Quarterly has written about Luck, Flesh, and Home. What about RULE OF LAW? Was there ever a better time to discuss that?”

I’m neither prescient nor wise beyond my years, but lo and behold, what to my wondering eyes should appear upon receiving the LQ spring issue recently? RULE OF LAW! Ahh. Great minds think alike. Or at least think. Sometimes.

This subject is worth scrutiny. Let us begin with the table of contents. Greeks and Romans are represented, among them Plutarch, both Greek and Roman. Napoleon Bonaparte. (Have you heard of Napoleonic Law? Perhaps we will be enlightened.) David Frost and Richard Nixon. I suspect there will be minds that don’t think alike. Frederick Douglass for the former slave and abolitionist perspective. Cotton Mather for Puritan’s progress.

Anne Boleyn may have insight on her pending demise. Chilling. Franz Kafka, always thought provoking to me. The Egyptian Book of the Dead and The Mahabharata. We can learn from the Ancients, I’m sure.

John Marshall, Nietzsche, Lewis Carroll, Kant, Locke, (notice how philosophers are recognizable without first names?), Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Elizabeth I, Catherine the Great, John Paul Stevens (who better to speak on law than U.S. Supreme Court Justices?).

This promises to be an intriguing issue.

Lewis Lapham’s Preamble is titled Due Process. Not everyone has founded and named a quarterly literary journal for himself. Mr. Lapham’s command of the Queen’s English often leaves me scrambling for a deciphering dictionary or trying to determine if a lengthy, lofty string of words is a complete sentence. (Sometimes not, I swear.) He likes to intersperse catchy metaphors and phrases in his prose, as he does in this Preamble:

“The funeral orations make a woeful noise unto the Lord…”

“…hundreds of millions of rules and regulations… tell us how, when, and with whom to tote the barge and lift the bale…”

My sense is that he tries to be fair and balanced but definitely does not lean toward the Conservative political spectrum. I was surprised he wasn’t more vocal in the run up to the Presidential election, but I think he has removed his self-constraint and is vocal now:

“To pick up on almost any story in the news these days… is to be informed… that the rule of law is vanished from the face of the American earth. So sayeth President Donald J. Trump, eight or nine times a day to his 47 million followers on Twitter. So sayeth also the plurality of expert witnesses in the court of principled opinion… testifying to the sad loss of America’s democracy, a once upon a time “government of laws and not of men.””

“…Trump’s loud and foul mouth…”

“…an unscripted and overweight canary flown from its gilded cage, telling it like it is when seen from the perch of the haves looking down on the birdseed of the have-nots.”

The gloves are off.

“In the world according to Trump—as it was in the worlds according to Ronald Reagan, George Bush elder and younger, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama—the concentrations of wealth is the good, the true, and the beautiful. Democracy is for losers.”

“The framers of the Constitution were of the same opinion.” … “With Plato the framers shared the assumption that the best government… incorporates the means by which a privileged few arrange the distribution of property and law for the less fortunate many.”

“…John Jay, chief justice for the Supreme Court, observed that “those who own the country ought to govern it.””

Indeed, the Internet informs us:

“Voting Before the Revolution

For the most part, American colonists adopted the voter qualifications that they had known in England. Typically, a voter had to be a free, adult, male resident of his county, a member of the predominant religious group, and a “freeholder.” A freeholder owned land worth a certain amount of money. Colonists believed only freeholders should vote because only they had a permanent stake in the stability of society. Freeholders also paid the bulk of the taxes. Other persons, as the famous English lawyer William Blackstone put it, “are in so mean a situation as to be esteemed to have no will of their own.”

Becoming a freeholder was not difficult for a man in colonial America since land was plentiful and cheap. Thus up to 75 percent of the adult males in most colonies qualified as voters. But this voting group fell far short of a majority of the people then living in the English colonies. After eliminating everyone under the age of 21, all slaves and women, most Jews and Catholics, plus those men too poor to be freeholders, the colonial electorate consisted of perhaps only 10 percent to 20 percent of the total population.”

( http://www.crf-usa.org/bill-of-rights-in-action/bria-8-1-b-who-voted-in-early-america )

I don’t know about ‘no will of their own’, but a stake in the game? Some merit perhaps, but try to change that now? No way. Evolution for better, or devolution for worse.

Mr. Lapham continues, discussing the Founding Fathers view of property as essential to liberty.

“By the word liberty, they meant liberty for property, not liberty for persons, and by the end of the summer of 1787 the well-to-do gentlemen in Philadelphia had drafted a document hospitable to their acquisition of more property.”

Was the United States founded on greed, or was it founded on motivation? “But unlike our present-day makers of money and law, the founders were not stupefied plutocrats. They knew how to read and write (in Latin or French, if not also in Greek), and they weren’t consumed by an all-consuming desire for wealth.”

They were wealthy. George Washington’s net worth was $580 million, inflation-adjusted to 2016. Thomas Jefferson’s was $234 million. This was when the U.S. population was 4-7 million people ( https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Census ), not 308 million as of 2010. Likely they rode their horse to town and mingled with less wealthy people (nearly everyone else?).

I read history via Lapham’s Quarterly to learn the past, understand the present, and ponder the future. My goal during this administration (presidential?) is to survive it. Will our constitutional republic survive it? We have a dictatorial president, and a dysfunctional congress of 535 members who failed at getting things done long before the current dictate-er arrived. Will the next election find us whip-sawing in the other direction to elect someone firmly embedded in far-left progressive socialism, the modern metamorphosis of old school communism, led, perhaps, by the occasionally rabid pit bull of a woman Elizabeth Warren? (Kidding of course.) That would be just as bad I think.

Hold on to your hats. It’s going to be a ride.

If you think Lewis Lapham’s Preamble deserves further inspection, it is available online at https://www.laphamsquarterly.org .

This issue may become a favorite. Stay tuned, as it is to.. be.. continued…

[Unless otherwise credited all quotes above are from the Preamble in the current issue.]

The standard notes:

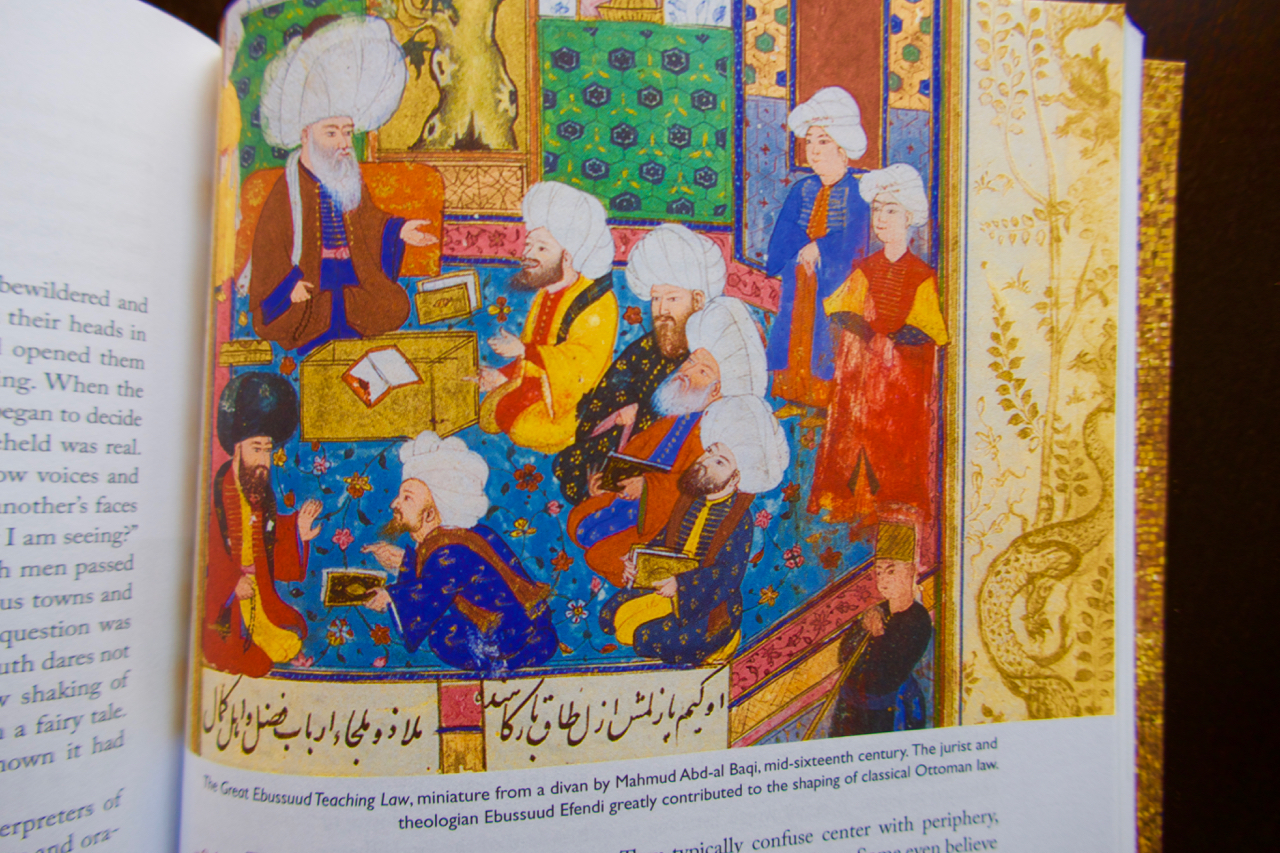

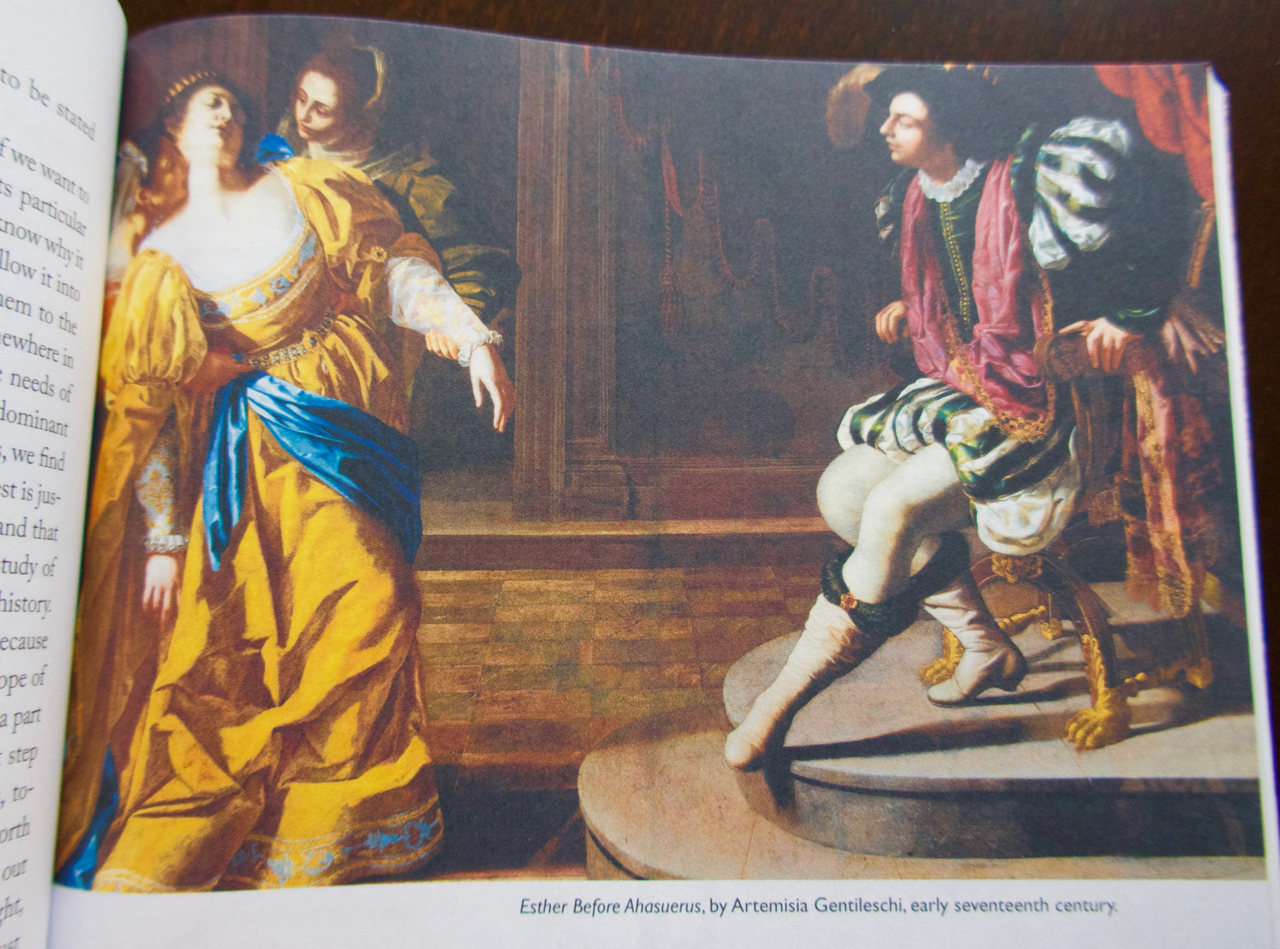

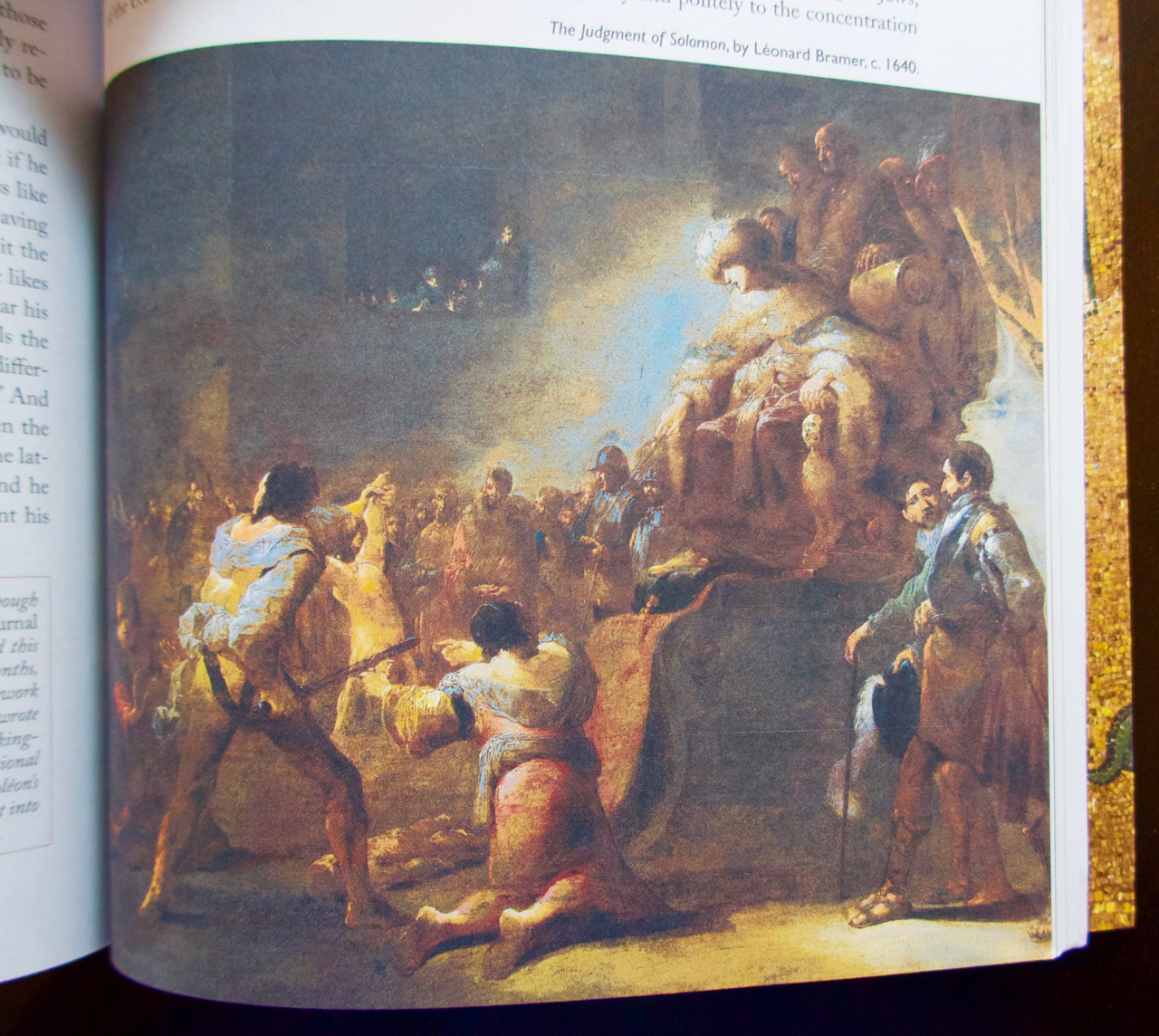

1. Since L.Q.’s inception with the Winter 2008 issue its size is always 7″ x 10″ x 1/2-17/32″. It is white-covered, printed on high quality paper throughout, with richly printed reproductions of fine art from time immemorial, and 221 pages up to a page or two of addenda at the back.

2. Each issue contains extracts about the title topic from great authors and thinkers spanning all recorded history. It begins with an eloquent, to a fault, preamble/introduction by editor Lewis Lapham. The main body is called Voices In Time and contains 3 or 4 subcategories of the topic with about 25 extracts per section. Noteworthy sidebars, side quotes, and depictions of appropriate art from the ages are liberally distributed throughout. Several extended contemporary essays bring up the rear. There are several other small sections every issue (Among the Contributors, Conversations, Miscellany, ‘The Graphic’).

3. Per the L.Q. website:

“Lapham’s Quarterly embodies the belief that history is the root of all education, scientific and literary as well as political and economic. Each issue addresses a topic of current interest and concern—war, religion, money, medicine, nature, crime—by bringing up to the microphone of the present the advice and counsel of the past.”

4. I encourage all to subscribe to this fine publication. It is a rich supplement to anyone’s reading.

Our republic is fascinating and so is this review. Lok forward to the continuation….

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Cindy.

LikeLike